|

![[Koralia Penakos Havas with stepdaughters and son]](../FamHavas-9.jpg)

![[Havas siblings, Limnos Greece]](../FamHavasSisters-2.jpg)

| |

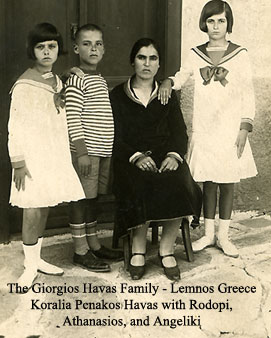

Angeliki (Angeline) Havas was born in 1917 in New Kensington, Pennsylvania. She and her sister

Rodopi, born a year later, were the daughters of Georgios (George) Athanasios Havas and Mercina Cacalis Havas.

Angeliki (Angeline) Havas was born in 1917 in New Kensington, Pennsylvania. She and her sister

Rodopi, born a year later, were the daughters of Georgios (George) Athanasios Havas and Mercina Cacalis Havas. The lives of Angeline Havas Pedas and her sister Rodopi Havas Angelidis were shaped by historical events including the 1920's influenza pandemic which killed their mother, World Wars I and II and Greece's political and economic upheavals. Working 12 hour days for less than 15 cents an hour they labored at open hearth furnaces which belched out smoke producing molten iron ore used to make steel for the manufacture of goods such as automobiles, kitchen utensils, radios, refrigerators and a steady stream of war supplies for the world wars raging in Europe. We honor our forbears. Their courage and sacrifice launched us, their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren into a world of unprecedented opportunities. Their odyssey continues through us.

| |

|

A journey from Lemnos, Greece to Western Pennsylvania

![[Giannis and Marika Havas]](../FamHavasGiannisMarika.jpg) Working as farm laborers during the Ottomon Turkish occupation, the Havas and Cacalis families cultivated vineyards, (the Horafia), raised goats and sheep and tilled the fertile land growing wheat, seseme, figs, grapes, olives, almonds, melons. They produced wine, olive oil, raisins and cheese.

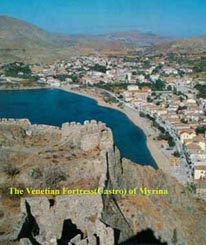

Working as farm laborers during the Ottomon Turkish occupation, the Havas and Cacalis families cultivated vineyards, (the Horafia), raised goats and sheep and tilled the fertile land growing wheat, seseme, figs, grapes, olives, almonds, melons. They produced wine, olive oil, raisins and cheese. The Havas family was from Androni near Petasos the mountain from which legend has it the women of Limnos hurled their hapless husbands into the sea. They also lived in the capital Mirina (Kastro) which is the island's main town and harbour. It has retained its ancient name, taken from one of the Amazons. Overlooking Mirina's enchanted bay are the ruins of a Venetian castle where once stood a temple to Artemis. Limnos was occupied by the Turks until 1912 when it was liberated by the Greeks. Despite living under the yoke of Turkish occupation for 500 years (Turkey at that time was known as the Ottomon Empire) the tenacious Limnians retained their Hellenic identity and Orthodox Christian religion. Except for the German occupation between 1941 and 1944 during World War II, Limnos has since remained part of Greece. From 1476 life under Turkish Ottomon rule was hopeless. They paid their taxes and labored, hopeing for nothing more than the means of subsistence from year to year. In its modern history, the battle of Limnos, which took place in its waters in 1913, during the Balkan War, was the event that liberated Limnos from Turkish domination. In 1920 Limnos became part of Greece. Greek families purchased their lands and homes from the departing Turks. The Havas vineyards "horafia" in Mirina along the beach owned by the Havas family were subsequently purchased by the Swiss who built expensive tourist bungalows. The price to George Havas family was $4,000.00 US dollars

| |

|

Androni, Limnos Greece ![[Havas family photos ]](../FamHavas-10.jpg)

![[Havas family photos ]](../FamHavas-11.jpg)

Born in 1889 Georgios Athanasios Havas was one of fourteen children,

seven of whom survived. His father, Athanasios, who died young had married his mother, Angeliki, when she was 14 years of age. Their seven surviving children

include:

![[Koralia Penakos Havas with Pedas family]](../FamHavasKoralia-2.jpg)

![[George Havas photos]](../FamHavasGeorge.jpg)

| |

|

From Limnos, Greece to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania On May 1, 1907 Georgios (George) Havas boarded the 5,633 ton SS Madonna in Naples arriving in steerage New York harbor on May 17. The ship's passenger manifest notes that Georgios Havas was a farm laborer, age 18, who was able to read but not write. He was a citizen of Limnos, Turkey (Greece was under Turkish occupation) who had been born in Androni (Mirina). He was unmarried. He vouched that he was neither a polygamist nor an anarchist. The condition of his mental and physical health was listed as 'good' and he had no visible marks of identification. His height was 5 feet 4 inches. The sum of money in his possession was $5.00. His final destination was Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where he would live with his brother Michalis Havas at 228 3rd Avenue. Their brother, Demitrios Havas, joined them, at age 18, in May 1910 arriving in the United States from Patras, Greece aboard the Themistocles.

| |

|

The dowry has been a Greek staple since Homeric times. The task of raising the dowry fell to fathers and brothers. Often a son's duty was to emigrate abroad to raise a dowry (prika) for his sister(s). Thereafter he was free to marry and begin his own life. Costas Cacalis arranged the marriage (proxinia) of his young sister Mercina Cacalis to Georgios Athanasios Havas. He paid for her shipboard passage from Greece to Western Pennsylvania. On May 31, 1916 Costas Cacalis married off his sister, Mercina Cacalis, to his friend, Georgios Athanasios Havas. Georgios Havas secured employment in the riverfront area of New Kensington, Pennsylvania where in 1888 the world's leading aluminium company, the Pittsburgh Reduction Company (Alcoa), produced its first aluminum. Aluminium, an abundant element in the earth's crust, was rare in its free form and difficult to separate from the rocks it was part of. Ancient Greeks used salts from this metal in dyeing and as astringents for dressing wounds. The invention of the process of isolating aluminium created an industrial metal suitable for commercial use. This spawned the factories and jobs which lured immigrants such as Georgios and Mercina Havas with the promise of a good life for themselves and their newborn daughters Angeliki (1917) and Rodopi (1918). The Havas family lived in a rented room at 8th Street and Fourth Avenue in New Kensington's industrial section a few blocks from the Allegheny River. Their future was full of promise.

| |

|

The epidemic began with a cough at an Army base in Kansas and spread across the globe. In the two years that this scourge ravaged the earth, a fifth of the world's population was infected by the deadly virus. It infected 28% of all Americans. World War I claimed an estimated 16 million lives. The influenza epidemic that swept the world in 1918 killed an estimated 50 million people. Of the U.S. soldiers who died in Europe, half of them fell to the influenza virus and not to the enemy. The virus was not discriminatory. Young and old, the weak and the strong - if they contracted that particular strain of the virus, dubbed the Spanish influenza, their chances of living were greatly reduced. Funeral directors couldn't keep up with the death toll, and carpenters were behind on building caskets. For days bodies were stacked without coffins on trucks because they couldn't be buried. Undertakers couldn't even get the bodies embalmed before another wave arrived. There were public outcries concerning attempts by some to line their pockets through the misery of others. Certain undertakers raised their prices by more than 500% as grieving families sought proper burials for their loved ones. Tales spread throughout the city of individuals being forced to pay fifteen dollars (instead of $5) to dig graves for their deceased family members.

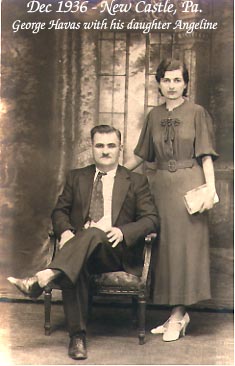

An unusual aspect of the Spanish flu was that it tended to target the young and healthy members of society. This was a complete reversal of the normal pattern with influenza, which normally attacked the old, the infirm and the young. Mercina Cacalis Havas, a young, vigorous, woman in the prime of her life was to become a statistic in the pandemic of death. The Federal Public Health Service reported more than 100,000 influenza cases during the week ending January 31, 1920. One of those victims was Mercina Cacalis Havas who, on January 28, 1920 had been admitted to Citizens General Hospital, New Kensington, Pennsylvania with symptoms of the devastating influenza. On Monday, February 2, 1920 at 1:00pm the 27 year old Mercina Cacalis Havas and the child she was bearing succumbed to the devastating influenza. Her death certificate, shown above, notes that a burial took place on February 4, 1920. Mercina's gravesite in New Kensington was never located. Photography was expensive and the taking of photos was limited to memorializing special events. The photo to the right depicting George Havas and his daughters, Angeliki and Rodopi, is presumed to have been taken after their mother's death, (February 1920) and prior to their March departure for Greece. Had their mother been alive she would have been included in the photo. The girls are shown wearing winter coats and each carried a small purse - possibly gifts from their uncles. At that time Rodopi was 18 months old and her sister Angeliki was 2 years and 9 months old. | |

|

The infuenza pandemic left George Havas with two orphaned daughters Angeliki and Rodopi. Neither girl has a personal memory of their mother, Mercina Cacalis Havas. They know of her through stories told them by family members. Their mother's short life began in Moudros on the Aegean Island of Limnos. Her trip to the United States had been sponsored by her brother, Costas Cacalis, who had arranged her marriage to his friend Georgios Havas. They were married May 31, 1916 and moved to New Kensington, Pennsylvania where they rented a room at 8th Street and Fourth Avenue, the industrial section of Westmoreland, near the Allegheny River. Mercina's sad and untimely death at age 27, during the influenza epidemic, devastated the Cacalis and Havas families. Mercina's mother, the blind Despina Sopiou Cacalis, born in 1865, was to outlive her daughter dying at age 80 in 1945. Mercina's father, Halalambos Cacalis, had died in Moudros in 1915 at age 61. Despina's granddaughter, Angeliki Havas, remembers how she waited at the pier to meet her Grandmother Despina Soupiou who was arriving from Egypt. The grandmother's first act was to hug and touch the young Angeliki's features as she was blind and had been told that the young Angeliki looked exactly as did her deceased daughter, Mercina Cacalis Havas - the mother of Angeliki and Rodopi.

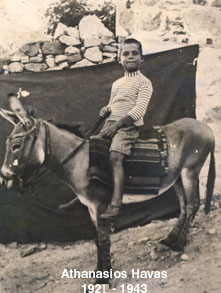

Angeliki and her sister Rodopi grew up with their stepmother and beloved stepbrother, Athanasios, on the ancient island of Limnos in the area known as Androni, Mirina. Koralia's father, Athanasios Penakos (Pinakos), lived with them where he slept on a cot on the porch. He sold watermelons and cucumbers from a tent which he pitched in the vineyards he had given Koralia as a dowry. The vineyards, where he raised grapes, wheat and vegetables, had been purchased from the departing Turks. Today this is a luxurious tourist area full of expensive Swiss bungalows. Angeliki was often assigned the task of looking after the tent while her Grandfather Athanasios Penakos and his donkey went into the fields to secure more produce. They would store the oversized watermelons in the deep well to keep them cool. Athanasios Penakos, supported his daughter Koralia Havas and her 3 children for many months during the depression in the United States when her husband, the unemployed Georgios Havas, was unable to send money to Limnos. One of his two sons, Giannis Penakos, was to perish in the battle to reclaim Smyrna. Angeliki had fond memories of her stepmother's cousin, Nicolas Bakalis who had also fought in Smyrna. He had the only phonograph player in Androni and his records could be heard throughout the village. Having been wounded in Smyrna he had to wear lifts to be able to walk. His brother, Giannis Bakalis, died from his wounds in Smyrna. Angeliki remembers him fondly. Once, when she was ill for 3 days, Giannis was told that her tooth hurt. He suggested Angeliki be taken to a doctor so Angeliki's stepmother gave Giannis a gold nugget and he took her to a doctor. It took several visits to remove the infection and thereafter he melted the gold nugget and capped the tooth with the gold filling. Angeliki remembers the 7 month period during America's depression when money from her Father was not forthcoming and they were short on food supplies he would bring bags of flour so the family could make bread. In 1920 George Havas was drafted into the Greek army to recapture the port city of Smyrna (Izmir). His pregnant wife Koralia remained in Limnos to give birth to their son, Athanasios, and to raise him and her two stepdaughters Angeliki and Rodopi. Georgios Havas never saw his son, who died in 1943 at age 22, from what was described as, "water on the lungs" - quite possibly pneumonia. The three year old Angeliki Havas would not see her father again until age nineteen when she returned to the United States, the land of her birth. The two year old Rodopi would reunite with her father in 1946 when she emigrated to the United States with her stepmother Koralia.

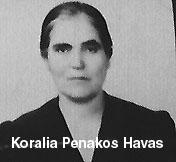

(Born Nov 16, 1901 - Deceased 1962)

Shortly after her marriage to Georgios Havas on September 1920 her husband was drafted into the Greek military where he fought for two years in the disastrous Asia Minor campaign to reclaim Smyrna (Izmir). He left the pregnant Koralia to give birth to their son and to care for her stepdaughters, Angeliki and Rodopi. She was not to see her husband for another 26 years. George Havas never saw his son, Athanasios, who died in 1943 at age 22. Father and son knew of each other only through photographs. As a citizen of Greece, Georgios Havas, who did not have U. S. citizenship, could not avoid Greece's compulsory three year military obligation. The brutal battle to liberate Smyrna ended in disaster on September 11, 1922, when the whole of seaside Smyrna was destroyed by fire during the horrible slaughter of its Greek Christian population. The war had claimed the lives of Koralia's brother, Gianni Pinakos, and her first cousin. Her brother had been wounded in battle at Smyrna. The retreating evzones were unable to rescue him as he lay dying from his wounds in the rain. Angeliki remembers a wounded cousin, Nikolas Bakalis, who returned from Smyrna unable to walk. He possessed the only phonograph player in Limnos.

Throughout the years Georgios Havas sent his earnings to his family in Limnos. He often complained that the value of money he sent to Greece was "cut in half" "Ta kopsane sta mesa". Every time the government devalued the Lira he lost half his net worth. Although illiterate, Koralia had proven to be a devoted, hard-working, frugal wife and mother. Unable to sign her name she would send Rodopi and Angeliki to the post office to pick up their father's letters. A superstitious woman she cautioned Angeliki and Rodopi not to mention that they received money - thus avoiding the curse of the 'evil eye'. When letters did not arrive she would have Angeliki take her cup to the gypsies to be 'read'. When Angeliki had her palm read she was told that she "would travel a great distance". The gypsy fortune teller told the young girl that Limnos was not in her future. Angeliki recalls that she was 14 years old when she learned, through classmates, that her 'real' mother had died in America and she was being raised by a stepmother. She sought out her uncle, Giorgios Cacalis, to verify this disturbing fact and indeed he confirmed that Angeliki and her sister Rodopi were the children of his sister, Mercina Cacalis Havas, who had died in New Kensington, Pennsylvania during the influenza epidemic of 1920. Having lived in Limnos since 1920, Angeliki and Rodopi Havas had no memory of the United States where they had been born in 1917 and 1918 respectively. This revelation shed light as to why their classmates often referred to Angeliki and Rodopi as the "Amerikanakia" (the little Americans). On one occasion Angeliki had been gathering almonds in the family vineyards when the bright sky darkened ominously. Her job had been to hit the upper branches of the tree with a long stick to cause the almonds to fall to the ground. Suddenly day began to turn into night - an eerie feeling which frightened her causing her to run home. It was a total eclipse of the sun which years later her son, the astronomer Ted Pedas, identified for her. The day was June 19, 1936 when the 19 year old Angeliki stood in the shadow of a 2 minute solar eclipse. Rodopi and Angeliki have vivid memories of the celestial event and the ensuing disturbance it created in Mirina where villagers hid indoors. World War II and the German occupation of Greece (1941-1944) created hardships for Koralia and her family. Rodopi had married the schoolmaster's son, Demitrios Angelidis and they had a son, Xenophone. Letters and money sent them from the United States were intercepted. In 1943 Athanasios Havas, the son of George Havas and Koralia took ill with what the family described as "water on the lungs" - probably pneumonia. Medication to treat his illness was not available to civilians during the war years. The desperate Koralia, sold off part of the family vineyards in Moudros (her dowry from her father) to purchase medicine from the Germans who occupied Limnos. Her son, born Aug 6, 1921 died in 1943. He died never having met his father - they knew each other through the exchange of letters and photos. On March 27, 1945 Georgios (George) Havas became a naturalized U.S. citizen. He was employed at Sharon Steel in Farrell, Pennsylvania . In 1946 he was able to bring his wife Koralia to the U.S along with his daughter Rodopi and her husband, Demetrios Angelidis, and their son Xenophon. Rodopi described the voyage aboard the SS Marine Shark as dreadful. It was a 12,000 ton refurbished army transport vessel operated by the United States Lines.The rooms had no private facilities, just bunk beds. The seas were rough and everyone spent most of the day praying. Once again life cheated Koralia Havas. Upon her arrival in the United States on May 10, 1946 a Warrant for her arrest was issued by the United States Department of Justice claiming she was in violation of immigration laws and was to be taken into custody and deported immediately. It took a year of correspondence from Greece to verify that Koralia Havas was legally married to George Havas. In 1948 Kolaria's husband George Havas, age 58, died of a sudden heart attack while working at the Sharon Steel mill in Farrell, Pennsylvania. Koralia left Farrell, Pennsylvania for a brief stay in the Bronx, New York with her stepdaugher Rodopi. Thereafter she returned to Limnos and Moudro where she died of cancer in 1962. ![[George Havas - Naturalization Document]](../FamHavasNaturalization.jpg)

|

![[George and Mercina Havas]](../FamHavas-Mercina.jpg) In 1910

In 1910 ![[Death Certificate - Mercina Cacalis Havas]](../FamHavasCertificate.jpg) The devastating 'Spanish Flu' epidemic engulfed the world from 1918 - 1920. There was no vaccine to combat the lethal strain of the virus.

The year 1918 would go down as one of unforgettable suffering and death. Within months, the deadly virus killed more people than any other illness in recorded history.

The devastating 'Spanish Flu' epidemic engulfed the world from 1918 - 1920. There was no vaccine to combat the lethal strain of the virus.

The year 1918 would go down as one of unforgettable suffering and death. Within months, the deadly virus killed more people than any other illness in recorded history.![[1920 George Havas with Angeliki and Rodopi]](../FamHavas1920.jpg) The 'plague of death' emerged in two phases. The first phase, known as the "three-day fever," appeared without warning. The disease began with a cough, then increasing pain behind the eyes and ears. Body temperature, heart rate, and respiration escalated rapidly. If not suppressed within the first 48 hours pneumonia quickly followed pushing victims into a rapid decline to death.

The two diseases inflamed and irritated the lungs until they filled with liquid, suffocating the patients in fluids produced in their own lungs and causing their bodies to turn a cyanotic blue-black.

The 'plague of death' emerged in two phases. The first phase, known as the "three-day fever," appeared without warning. The disease began with a cough, then increasing pain behind the eyes and ears. Body temperature, heart rate, and respiration escalated rapidly. If not suppressed within the first 48 hours pneumonia quickly followed pushing victims into a rapid decline to death.

The two diseases inflamed and irritated the lungs until they filled with liquid, suffocating the patients in fluids produced in their own lungs and causing their bodies to turn a cyanotic blue-black.

Initially the widowed Georgios Havas boarded with relatives who cared for his daughters along with their own children. Unable to find a suitable wife he took the two and half-year-old Angeliki (Angeline) and one year old

Initially the widowed Georgios Havas boarded with relatives who cared for his daughters along with their own children. Unable to find a suitable wife he took the two and half-year-old Angeliki (Angeline) and one year old

Koralia's life was not easy. Born November 16, 1901 Koralia lost her mother at age 13 leaving her to care for her father, Athanasios Penakos, and her brother, Gianni, who died in the war with Smyrna. Her sister, Malama, also died early in life. Koralia's biological son, Athanasios Havas, died at age 24 without having ever met his father. From her mother's death until her own in 1962 Koralia was clothed in black, the color of mourning. She remained uneducated, unable to read, write or count money.

Koralia's life was not easy. Born November 16, 1901 Koralia lost her mother at age 13 leaving her to care for her father, Athanasios Penakos, and her brother, Gianni, who died in the war with Smyrna. Her sister, Malama, also died early in life. Koralia's biological son, Athanasios Havas, died at age 24 without having ever met his father. From her mother's death until her own in 1962 Koralia was clothed in black, the color of mourning. She remained uneducated, unable to read, write or count money. The dream of returning to a peaceful family life had once again eluded Georgios Havas. Unable to return to Limnos he smuggled himself aboard ships where he found employment. On May 4, 1923 he boarded the ship, Estuania, returning to the United States where he hid for six years to avoid deportation. On March 27, 1945 Georgios (George) Havas became a naturalized U.S. citizen.

The dream of returning to a peaceful family life had once again eluded Georgios Havas. Unable to return to Limnos he smuggled himself aboard ships where he found employment. On May 4, 1923 he boarded the ship, Estuania, returning to the United States where he hid for six years to avoid deportation. On March 27, 1945 Georgios (George) Havas became a naturalized U.S. citizen. ![[Angeliki Havas 1920 - 1938]](../FamHavasAngeliki.jpg)

Angeliki Havas's dream was to depart Limnos for America. She pleaded with her Father, George Havas, to send her passage fare.

Angeliki Havas's dream was to depart Limnos for America. She pleaded with her Father, George Havas, to send her passage fare.

Efstathios Tsimpidis (Steve Pedas) and Angeliki (Angeline) Havas were married in Farrell, Pa. on Sunday, January 16, 1938 in the one room Greek church located above a storefront on Haywood Street. The wedding reception was held at the Italian Hall at 806 Spearman Avenue.

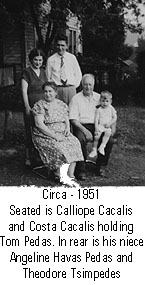

Efstathios Tsimpidis (Steve Pedas) and Angeliki (Angeline) Havas were married in Farrell, Pa. on Sunday, January 16, 1938 in the one room Greek church located above a storefront on Haywood Street. The wedding reception was held at the Italian Hall at 806 Spearman Avenue.  The Ancestral home of the Cacalis family is Moudros on the Aegean island of Limnos, Greece where Haralampos Cacalis (1854 - 1915)lived with his wife Despina Soupiou (1865-1945). They had five children - two sons, Georgios (George), who lived in Egypt, and

The Ancestral home of the Cacalis family is Moudros on the Aegean island of Limnos, Greece where Haralampos Cacalis (1854 - 1915)lived with his wife Despina Soupiou (1865-1945). They had five children - two sons, Georgios (George), who lived in Egypt, and

![[George Cacalis]](../Fam-CacalisGeorge.jpg)

![[Fotini Cacalis]](../Fam-CacalisFonte.jpg) George (Giorgios) Cacalis had moved from the island of Limnos to Egypt where he and his wife Despina and two daughters lived. He became successful baking bread. He, with his mother Despina and sister Fotini would vacation during the summer in Limnos. He is remembered by his nieces,

George (Giorgios) Cacalis had moved from the island of Limnos to Egypt where he and his wife Despina and two daughters lived. He became successful baking bread. He, with his mother Despina and sister Fotini would vacation during the summer in Limnos. He is remembered by his nieces, ![[Costas Cacalis]](../Fam-CacalisCostas.jpg)

![[Fania Cacalis]](../Fam-CacalisFania.jpg) Fotini's twin brother, Constantinos (Costas) attended school in Limnos through the third grade and tended his father's sheep. At age 16 he left Limnos for to Benha, Egypt where he joined his brother George. He was wearing shoes he borrowed from his mother. They were the same borrowed shoes his brother had worn and sent back to his mother. Both brothers worked at their Godfather's bakery making and delivering bread. At night they slept on top of the warm ovens to avoid the rats. A mishap occurred when Costas was delivering bread on the rain. He lost one of his mother's shoes in the muddy street and therefore could not return them to her.

Fotini's twin brother, Constantinos (Costas) attended school in Limnos through the third grade and tended his father's sheep. At age 16 he left Limnos for to Benha, Egypt where he joined his brother George. He was wearing shoes he borrowed from his mother. They were the same borrowed shoes his brother had worn and sent back to his mother. Both brothers worked at their Godfather's bakery making and delivering bread. At night they slept on top of the warm ovens to avoid the rats. A mishap occurred when Costas was delivering bread on the rain. He lost one of his mother's shoes in the muddy street and therefore could not return them to her.

![[The family of Haralambos and Despina Soupiou Cacalis]](../Fam-CacalisFamilyCollage.jpg)

The islands of the north eastern Aegean sea are the peaks of mountain tops of a once continuous territory that has been gradually submerged by the sea. The ancient Greeks made them sacred to the gods. The island's volcanic origins manifest themselves today in astringent hot springs.

The islands of the north eastern Aegean sea are the peaks of mountain tops of a once continuous territory that has been gradually submerged by the sea. The ancient Greeks made them sacred to the gods. The island's volcanic origins manifest themselves today in astringent hot springs.![[You Tube]](../YouTube.gif)