|

![[Rodopi and Angeliki]](../FamHavasSisters.jpg)

![[Rodopi and Angeliki Havas]](../FamHavasSisters-5.jpg)

![[George and Mercina Wedding]](../Fam-CacalisMercina.jpg)

![[George, Mercina, and Michalis]](../FamHavas-Mercina.jpg) Rodopi Havas was born 1918 into a world on the brink of peace. The decisive battles of World War I had been fought. Quiet descended on Europe for the first time in over four years with the armistice of November 1918. The horrors of the "the war to end all wars" had ended.

Rodopi Havas was born 1918 into a world on the brink of peace. The decisive battles of World War I had been fought. Quiet descended on Europe for the first time in over four years with the armistice of November 1918. The horrors of the "the war to end all wars" had ended. Born in New Kensington, Pennsylvania, Rodopi was the second daughter of Georgios (George) Athanasios Havas and Mercina Cacalis Havas. Their daughter, Angeliki, had been born a year earlier. Baptized in the Greek Orthodox Christian faith Rodopi was given her name by her Godfather, Evangelis Karagianis, who like Rodopi's parents had been born on the Aegean Island of Lemnos, Greece. The name Rodopi is of Thracian origin. It is the old and modern Greek name for the mountains which extend 200 miles through Greece and Bulgaria. In antiquity the chain formed the border between Thrace and Macedon. The Rodopi prefecture is rich in Greek mythology. This was the birthplace of the lyre player Orpheus and his wife Eurydice. The Rodopi mountains were the scene of battle between Zeus and the Giants who sought to overthrow him. In this land of legends local people willingly tell you of Queen Rhodopi of Thrace, the wife of King Haemus who was changed into the Rodopi (Rhodope) Mountains by Zeus as a punishment. Famous Thracians included Democritus the Greek philosopher and mathematician who contributed the atomic theory, Herodicus the Greek physician of the fifth century BC who is considered the founder of sports medicine and Spartacus a Thracian enslaved by the Romans who led a large slave uprising of escaped gladiators and slaves in 73-71 BC.

For as far back as anyone can remember the families of George Havas and Mercina Cacalis had lived on the island of Lemnos, Greece. The Havas family from the cheerful seaside town of Androni (Mirina) and the Cacalis family from Moudros, the island's second largest city. The dowry has been a Greek staple since Homeric times. Poor Greek families sent their sons, some as young as fourteen, to the United States where they were expected to work hard to provide dowries for their sisters. Once the son accomplished his duty he was free to marry and begin his own life. In 1907 Costas Cacalis emigrated from Greece to the United States and settled in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania where he met George Havas. Although from the same Aegean island - the Cacalis and Havas families became acquainted at Aliquippa's Jones & Laughlin Steel mill where Costas Cacalis and George Havas were employed. Costas Cacalis arranged the marriage (proxinia) of his young sister Mercina Cacalis to George Athanasios Havas. He paid for her shipboard passage from Greece to Western Pennsylvania. On May 31, 1916 Costas Cacalis married off his sister, Mercina Cacalis, to his friend, George Athanasios Havas. In later years George Havas recalled the years 1916 to 1919 as his happiest. They had been blessed with two daughters, Angeliki (1917) and Rodopi (1918) with a third child on its way. George Havas and his wife, Mercina Cacalis Havas, had set the foundation to achieve their American dream.

The Havas family lived in a rented room at 8th Street and Fourth Avenue in New Kensington's industrial section a few blocks from the Allegheny River. Their future was full of promise.

In 1918, World War I was in its final spasms, and peace was on the horizon. President Wilson's peace program ended with Germany's surrender. Yet hundreds of thousands of Americans died that year, and they weren't war casualties. Between 1918 and 1920, as many as 50 million people worldwide died from the devastating 'Spanish Flu' epidemic which engulfed the world. An estimated 675,000 of those deaths occurred in the United States, where the killer bug, for which there was no vaccine, took the lives of more people than American soldiers in the war - 10 times as many. The World Health Organization called it "the most deadly disease event in the history of humanity," killing more than even the Black Death - the Bubonic Plague of the Middle Ages (1347-1351). The virus was not discriminatory. Young and old, the weak and the strong - if they contracted that particular strain of the virus, dubbed the Spanish influenza, their chances of living were greatly reduced. Funeral directors couldn't keep up with the death toll, and carpenters were behind on building caskets. Bodies were stacked up for days because they couldn't be buried. Undertakers couldn't even get the bodies embalmed before another wave arrived. There were public outcries concerning attempts by some to line their pockets through the misery of others. Certain undertakers raised their prices by more than 500% as grieving families sought proper burials for their loved ones. Tales spread throughout the city of individuals being forced to pay an exorbitant fee of fifteen dollars to dig graves for their deceased family members.

1893 - 1920

On May 31, 1916 Costas Cacalis had married off his sister, Mercina Cacalis, to his friend Georgios (George) Havas. Their first daughter, Angeliki, born in 1917 was followed by Rodopi born in 1918. That same month the United States Surgeon General Rupert Blue dispatched advice to the press on how to recognize symptoms of the so-called Spanish Influenza. October 1918 would be the deadliest month in the nation's history as 195,000 Americans fall victim to influenza. The first wave of influenza appeared early in the spring of 1918 in Kansas and in military camps throughout the United States. The first reported case had occured on March 11 when an Army private at Fort Riley, Kansas complained of a cough, fever, sorethroat and headache. He was diagnosed as having a strain of flu that was called Spanish Influenza (since it was erroneously believed the strain had originated in Spain). By weekend the camp hospital reported 500 similar cases. The virus moved from the military population to the general public. Reports were coming out of Boston of a virulent, deadly influenza. One thousand people died there by the end of September 1918. Philadelphia lost more than 4,500 residents to the virus by late October. Influenza spreading amongst men living in close quarters did not particularly alarm the public health officials of the day. Little data existed at the time to indicate a sizable spread among the civilian population. Besides, the nation had bigger matters on its mind. There was a war to win. The influenza had already established a foothold in military camps from Massachusetts to Louisiana and was starting to make its presence felt as far west as Camp Kearny in California. When it began to cut its deadly path across the United States in the autumn of 1918, it did so with such speed and fatal efficiency that some believed sinister forces to be at work. Rumors emerged blaming the Germans for releasing deadly influenza germs on American soldiers. As proven later the virus originated in the United States and was spread around the globe by U.S. troops mobilized for World War I. In 1918 the nation's top medical specialists had not yet reached a consensus on exactly what influenza was. Before trying to define the disease for an alarmed citizenry, public health officials debated amongst themselves. A large part of the burden of informing and protecting the public fell to 50-year-old Rupert Blue, Surgeon General of the United States Public Health Service. Blue was in sole command of 180 health officers and 44 quarantine stations throughout the country. The flu prevented day-to-day operations from going smoothly. Officials feared mass hysteria in major cities. The flu interrupted the activities of the U.S. Food Administration responsible for rationing during World War I. Problems arose concerning available funds to counteract the spread of infection. Money sources were dwindling on local levels, supplies of medicine were growing scarce, and many health care providers were becoming sick from exposure to the virus. At one point, the Bell Telephone Company, where 28% of their work force was absent due to the influenza, restricted calls of a non-medical nature. Prices for medications rose. Congress approved a special $1 million fund to enable the U.S. Public Health Service to recruit physicians and nurses to deal with the growing epidemic. US Surgeon General Rupert Blue set out to hire over 1000 doctors and 700 nurses with the new funds. The war effort, however, made Blue's task difficult. The nation's ranks of medical professionals, doctors and nurses, were engaged overseas lending care to fighting soldiers. Able-bodied doctors were summoned from retirement, while novice medical students were plucked from their studies to tend to the sick. The highly contagious flu spread rapidly. Legislation was passed banning public coughing, sneezing and spitting. Citizens were urged to stay indoors and avoid congested areas. Masks of four-ply surgical gauze (soaked in camphor)which tied around the mouth and nose were given out to all residents of the city. Some would cut holes in the masks to enable them to smoke. Civil libertarians fought the law on the grounds that it was unconstitutional. The penalty for disregarding the law was a fine of one hundred dollars and thirty days in jail. Flu ordinances were imposed. Washington D.C. enacted a law that made it illegal for those stricken to appear out of doors and out of one's home. Pennsylvania issued a statewide ban closing theaters, saloons, schools, libraries churches, and public meeting houses. Stores could not hold sales, funerals were limited to 15 minutes. Some towns required a signed certificate to enter and railroads would not accept passengers without them. The public was implored to develop the habit of washing their hands before every meal and paying special attention to general hygiene. Nervous and physical exhaustion should be avoided. Gargling with a variety of dubious elixirs was encouraged as was rinsing everything with chlorinated soda and a mixture of sodium bicarbonate and boric acid. Folk remedies included stuffing salt up the nose and wearing bags of garlic around the neck. The Colgate company placed ads detailing twelve steps to prevent influenza. Among the recommendations: chew food carefully and avoid tight clothes and shoes. In November 11 of 1918 the end of the war enabled a resurgence of the influenza. As people celebrated Armistice Day with parades and large partiess, a complete disaster from the public health standpoint, a rebirth of the epidemic occurred in some cities. Even President Woodrow Wilson suffered from the flu in early 1919 while in Paris negotiating the crucial treaty of Versailles to end the World War An unusual aspect of the Spanish flu was that it tended to target the young and healthy members of society. This was a complete reversal of the normal pattern with influenza, which normally attacked the old, the infirm and the young. Mercina Cacalis Havas, a young, vigorous, woman in the prime of her life was to become a statistic in the pandemic of death. The Federal Public Health Service reported that more than 100,000 influenza cases were reported during the week ending January 31, 1920. One of those victims was Mercina Cacalis Havas who, on January 28, 1920 had been admitted to Citizens General Hospital, New Kensington, Pennsylvania with symptoms of the devastating influenza. On Monday, February 2, 1920 at 1:00pm the 27 year old pregnant Mercina Cacalis Havas succumbed to the devastating influenza. Her death certificate, shown above, notes that a burial took place on February 4, 1920. Mercina's gravesite in New Kensington was never located. The influenza seemed to slip away as mysteriously as it had arrived. The doctors of that day knew no more about the flu than 14th century Florentines had known about Black Death. To this day little is known about the origin or nature of the killer virus.

(Mercina's mother and siblings)

![[The family of Haralambos and Despina Soupiou Cacalis]](../Fam-CacalisFamilyCollage.jpg) Mercina Cacalis was born in 1893 in Moudros on the Aegean Island of Lemnos. Her trip to the United States had been sponsored by her brother, Costas Cacalis, who had arranged her marriage in 1916 to George Havas. Mercina died in 1920 in New Kensington, Pennsylvania at age 27 during the influenza epidemic. Mercina's parents and four siblings (shown above) outlived her. Mercina's father, Halalambos Cacalis, died in Moudros Greece in 1915 at age 61. Mercina's mother, the blind Despina Sopiou Cacalis, born in 1865, was to outlive her daughter dying at age 80 in 1945. Siblings who survived Mercina included a sister, Fotini, and two brothers, Costas (Constantinos) Cacalis (Aliquippa, Pennsylvania) Georgios Cacalis. A sister, Fania, had died at age 20 of back injuries when she slipped while loading a donkey and fell backwards landing on a rock while working in the fields. Fania, who had been engaged to be married, suffered for days before succumbing to her injuries. Despina and Fania (mother and daughter) are buried in Moudro, on the island of Lemnos Greece.

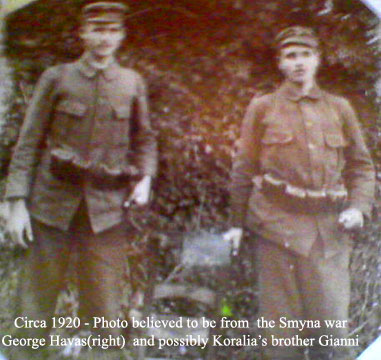

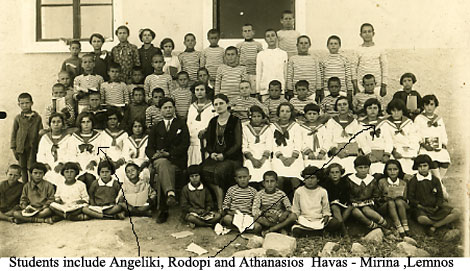

In New Kensington, the widowed George Havas boarded with relatives who cared for his daughters an arrangement which did not work as they had children of their own to raise. On March 14, 1920 a heart-broken George Havas and his young daughters departed America aboard the steamship SS Estuania returning to Lemnos Greece, the Aegean island of his birth. Family members tell how he packed a trunk full of diapers which were tossed overboard when used during the difficult voyage with two young girls in tow. Photography was expensive and the taking of photos was limited to memorializing special events. The photo to the left depicting George Havas and his daughters, Angeliki and Rodopi, is presumed to have been taken after their mother's death, (February 1920) and prior to their March departure for Greece. Had their mother been alive she would have been included in the photo. The girls are shown wearing winter coats. At that time Rodopi was 18 months old and her sister Angeliki was 2 years and 9 months old. The year 1920 was fraught with hardship for George Havas. On February 2, 1920 his wife, Mercina Cacalis Havas, had died in New Kensington Pennsylvania during the influenza epidemic. On September 3, 1920 George Havas married Koralia Pinakos in Lemnos Greece. They moved into the house which was given as a dowry by Koralia's father, Athanasios Pinakos. That same year George Havas was drafted to fight the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 to reclaim Greece's ancient city of Smyrna (Izmir today). As a citizen of Greece (he did not have U.S. citizenship) he could not avoid his military obligation. He left behind a pregnant wife who gave birth to a son, Athanasios. He never saw his son who died of pneumonia at age 22 during the German occupation when medication was unable. Twenty-six years would pass before George Havas again saw his wife, Koralia, and daughter Rodopi. Sixteen years would pass before he was reunited with his daughter, Angeliki. Rodopi and Angeliki speak lovingly of their stepmother, Koralia, and her many sacrifices in raising them and their stepbrother, Athanasios. Rodopi recalls that her stepmother would go without eating to be able to purchase items for the family. It was not until they reached their teens when Rodopi and Angeliki learned, through classmates,that their mother, Mercina Cacalis Havas, had died in America and they were being raised by a stepmother.

Having survived Greece's disastrous war to reclaim Smyrna George Havas was unwilling to return to Greece least he again be drafted. From the war ravaged and burned out city of Smyrna he somehow managed to smuggle himself back into the United States arriving in Boston aboard the Estuania on May 4, 1923. He secured employment in the steel mills of New Castle and Farell Pennsylvania. He supported his family in Lemnos. Rodopi, whose task it was to collect the mail from the postal office, relates how the funds ceased arriving during the depression when her father was unemployed and again during the German occupation of Lemnos during World War II when mail could not penetrate the war zone. During this time it was Koralia's father and uncles who provided the flour, sugar, oil and food to sustain the family. In 1936 George Havas was reunited in Pennsylvania with his daughter Angeliki. He never saw his son, Athanasios Pinakos Havas, who died of pneumonia in 1943 at age 22. In 1945 George Havas was reunited with his wife, Koralia, and daughter Rodopi in the United States. He died of a massive heart attack in 1948 while working at the Carnegie Steel plant in Farrell, Pennsylvania.

The orphaned sisters, Rodopi and Angeliki Havas, grew up in Lemnos surrounded by the loving extended families of their father, George Havas, of their deceased mother, Mercina Cacalis Havas, and of their stepmother, Koralia Pinakos Havas. George (Georgios) Havas, father of Rodopi and Angeliki, was one of seven surviving children of the fourteen born to Athanasios and Angeliki Havas in Androni, Lemnos. George and his three brothers Athanasios, Demitrios and Michalis had emigrated from Lemnos to the United States - George in 1907 and Dimitrios in 1910. His brother Constantine, a farmer, and two sisters Fotini and Maria remained in Lemnos. These siblings and his mother, the deaf Angeliki, showered their love on the orphaned daughters of George and Mercina Havas. Although they never met their paternal grandfather who died early in life, both Rodopi and Angeliki share fond memories of their paternal grandmother, Angeliki Havas, as a woman with the rare knack of mending the broken bones of injured animals. If a lamb or goat broke a leg she was able to reset it. On one occassion the young Angeliki recalls her Grandmother Angeliki (for whom she was named) scolding her to stop swinging from a rope she had flung over the branch of the fig tree. As predicted the branch broke. Angeliki fell on her forehead causing a scar which she bears to this day.

Funerals in Greece, for reasons of climate, are carried out as soon as possible after death and are announced by the village churchbells. The dead are placed in the earth for three to five years (longer if the family can pay) after which time the bones are dug up and placed in the family skeleton box to make room for the next resident. Sugared wheat called 'Kouvila' is given out after the funeral ceremony. Rodopi tells that it was not uncommon for mischievous school boys to break into the storage room where the boxed skeletons were housed and make off with skeleton heads which they would throw at the girls to frighten them. The extended family in Lemnos included members of the Cacalis family. Mercina Cacalis-Havas (1893-1920), the biological mother of Rodopi and Angeliki, was the daughter of Haralambos Cacalis and his wife Despina Souiou Cacalis (1865 - 1945). Mercina had two sisters, Fania, who died young from an injury, and Fotini. Her two brothers were Georgios Cacalis, a baker who lived in Egypt, and Costa Cacalis one of the first Greek immigrants to settle in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania. Rodopi and Angeliki remember their grandmother Despina who was blind. They also have fond memories of Georgios Cacalis who would bring them trinkets from Egypt during his summer holidays in Lemnos. Rodopi and her sister Angeliki had no memory of America where they were born and lived the first few years of their lives. Growing up in Lemnos Greece their playmates often referred to them as the "Americanakia" (the Americans). Nor did they have any memory of their father who in 1920 was drafted into the Greek army and subsequently relocated in America. Letters and photos were their only communication. One photo particularly displeased George Havas who reprimanded his wife for cutting short Rodopi and Angeliki's hair. In America, he wrote, short hair was worn by prostitutes, flappers, and women of ill repute.

The tradition of music in Greece goes back thousands of years. Island folksongs "Nissiotika" have certain dances and rhythms which trace back to antiquity. The "Syrtos" and "Kalamatianos", depicted on ancient Greek vase paintings, are a favorite of the island dances while the jumping dances "Pidiko" represent the rugged mountain areas. In his dances and songs, accompanied with traditional instruments, the Greek tells of his joys, his sorrows, and his inspirations. The villagers on the island of Lemnos celebrate various local and religious feasts throughout the year. Rodopi recalls the first day of May when she would climb the low hills of Lemnos to pick amarantos, a wild flowering shrub, which she and the villagers would weave into wreaths, called kakanoures, to place on the door of their homes. "Amaranthos" is a Greek word meaning never withering, as the dried flower maintains its freshness and pink cluster of flowers throughout the year. In Greek mythology it was sacred to the Olympian Goddess Artemis. Because of its unfading quality the amaranth wreath was a symbol of immortality which would bless the home's occupants with life.

Very high quality cotton was produced in Limnos. It was in great demand and was considered to be second best to Egyptian cotton. An impressive stone building in Myrina was used as a cotton gin to separate the cotton fiber from its seed. Wool from the island's sheep was also used to make sweaters. As a child Rodopi enjoyed making clothes for her dolls. Unable to afford expensive fabric she used nets discarded by local fishermen. Her stepmother had arranged for both Rodopi and her older sister Angeliki to take sewing lessons. Local dressmakers would enlist students to assist them in exchange for being taught the trade. Rodopi, one of the more promising students, remembers working in the home of a dressmaker where she learned the art of dressmaking. The dresses worn by Rodopi and her sister in photos, including her wedding dress, were her handiwork. Later in life,when she relocated to New York City, she found employment as a dressmaker working in the midtown Rockefeller Center area. Rodopi developed a keen sense for business. Unable to read or write Koralia entrusted her stepdaughter to negotiate family purchases, a sack of flour, sugar, oil and butter, at the agora. At the post office she would retrieve letters sent from her father in America which included money he would send to the family.

Tuesday (Tritiatiki) is considered the unluckiest day during the week for the Greek people. It was on this day on Tuesday May 29th 1453 that the city of Constantinople fell to the "Ottoman Turks". Throughout her life Rodopi avoided cutting fabric to begin sewing a new dress, or transacting business on a Tuesday. The 'Evil Eye' is an ancient superstition. It is a negative power which everyone carries within them. If one stares too long on a person or object, from admiration or envy, they may unconsciously inflict damage through this power which channels itself through the eye. The victim will suddenly get a headache, dizzy spell, faint, or even die, depending on the Evil Eye's strength and the victim's susceptiblility. To get rid of the spell, you must find a person who can break it. Rodopi's stepmother, Koralia, believed that someone can catch the Evil Eye, or matiasma, from someone else's jealous compliment or envy. Koralia would caution her stepdaughters, Rodopi and Angeliki, not to mention that they received money from America least they cast the 'Evil Eye' on the Havas family. To avoid the matiasma, one can wear a charm such as a small blue marble glass with an eye painted on it. Blue is considered a protective colour that wards off the evil of the eye. Garlic is another way to ward off the evil eye, and one can sometimes see it hanging in a corner of the house. Spitting is believed to be very effective against The Evil Eye. If someone compliments a Greek to avoid the Evil Eye they may spit three times onto themselves, and may say to the person "Ptew, Ptew Ptew mi me matiasis", which basically says, "I'm spitting on myself so that you do not cause the Evil Eye to come upon me." It is customary for Greeks to spit to ward off evil. If a Greek hears bad news they may spit on themselves three times to ward of the possibility of anything bad happening to themselves. Spitting is also commonly used to avoid misfortune. The Greek fishermen could be seen spitting in their nets before lowering them into the sea so they ward off evil and get good days' catch. Superstition has it that spitting chases the devil and the misfortune away. That is why when someone talks about bad news (deaths, accidents, etc...) the others slightly spit three times saying "ftou, ftou, ftou".

|

![[New Kensington Map]](../FamHavasMapKensington.jpg) Employment opportunities lured George Havas and his bride Mercina Cacalis Havas to New Kensington, a city founded in 1891 on the Allegheney River. With its advantage of level land and access to the river and railraod, this western Pennsylvania city was a prime location for industries including machinery, milling, brewing, ceramics, and concrete. Schools and Churches flourished to accommodate New Kensington's 12,000 inhabitants. Early achievements included a railroad station, the 9th Street bridge, a passenger boat that navigated the Allegheny River, a street car, the "Kensington Dispatch" newspaper, a fire department, hotel, opera house, and a local chapter of the YMCA.

Employment opportunities lured George Havas and his bride Mercina Cacalis Havas to New Kensington, a city founded in 1891 on the Allegheney River. With its advantage of level land and access to the river and railraod, this western Pennsylvania city was a prime location for industries including machinery, milling, brewing, ceramics, and concrete. Schools and Churches flourished to accommodate New Kensington's 12,000 inhabitants. Early achievements included a railroad station, the 9th Street bridge, a passenger boat that navigated the Allegheny River, a street car, the "Kensington Dispatch" newspaper, a fire department, hotel, opera house, and a local chapter of the YMCA. ![[Death Certificate - Mercina Cacalis Havas]](../FamHavasCertificate.jpg) The 'plague of death' emerged in two phases. The first phase, known as the "three-day fever," appeared without warning. The disease began with a cough, then increasing pain behind the eyes and ears. Body temperature, heart rate, and respiration escalated rapidly. If not suppressed within the first 48 hours pneumonia quickly followed pushing victims into a rapid decline to death.

The two diseases inflamed and irritated the lungs until they filled with liquid, suffocating the patients in fluids produced in their own lungs and causing their bodies to turn a cyanotic blue-black.

The 'plague of death' emerged in two phases. The first phase, known as the "three-day fever," appeared without warning. The disease began with a cough, then increasing pain behind the eyes and ears. Body temperature, heart rate, and respiration escalated rapidly. If not suppressed within the first 48 hours pneumonia quickly followed pushing victims into a rapid decline to death.

The two diseases inflamed and irritated the lungs until they filled with liquid, suffocating the patients in fluids produced in their own lungs and causing their bodies to turn a cyanotic blue-black.![[1920 George Havas with Angeliki and Rodopi]](../FamHavas1920.jpg) The most devastating epidemic in U. S. history left George Havas with two motherless daughters, three year old

The most devastating epidemic in U. S. history left George Havas with two motherless daughters, three year old  The brutal battle to reclaim Smyrna, known as the 'War in Asia Minor', claimed the lives of many Greeks including those of Koralia's brother, Gianni, and her first cousin. Koralia Pinakos's life was a sad one. Born November 16, 1901 she lost her mother at age 13 leaving her to care for her father, her brother, Gianni (who died in the war with Smyrna) and sister, Malama, who also died early in life. Koralia's son, Athanasios died at age 22. From her mother's death until her own in 1962 Koralia was clothed in black, the color of mourning. She remained uneducated, unable to read, write or count money.

The brutal battle to reclaim Smyrna, known as the 'War in Asia Minor', claimed the lives of many Greeks including those of Koralia's brother, Gianni, and her first cousin. Koralia Pinakos's life was a sad one. Born November 16, 1901 she lost her mother at age 13 leaving her to care for her father, her brother, Gianni (who died in the war with Smyrna) and sister, Malama, who also died early in life. Koralia's son, Athanasios died at age 22. From her mother's death until her own in 1962 Koralia was clothed in black, the color of mourning. She remained uneducated, unable to read, write or count money.

Lemnos is a Greek island of the northeast Aegean Sea located opposite Troy. The hilly island rises to 1,540 ft at its highest point capped with the ruins of the Venetian fortress built in 1207 on the site of Aphrodite's ancient acropolis. The Havas family lived in Mirina, the island's chief town and principal port which is also called Kastro.

Lemnos is a Greek island of the northeast Aegean Sea located opposite Troy. The hilly island rises to 1,540 ft at its highest point capped with the ruins of the Venetian fortress built in 1207 on the site of Aphrodite's ancient acropolis. The Havas family lived in Mirina, the island's chief town and principal port which is also called Kastro.  Rodopi recalls that she was 8 years old when her paternal grandmother died. The teacher excused Rodopi and

Rodopi recalls that she was 8 years old when her paternal grandmother died. The teacher excused Rodopi and ![[Rodopi and Angeliki]](../FamHavasSisters-3.jpg) Many of the Greek customs and traditions have their roots in the Greek Christian Orthodox religion. The church plays an important role in the daily lives of the Greeks, and religion and tradition are intrinsically interwoven. Easter is the most important religious holiday in Greece, and is preceded by 40 days of fasting.

Many of the Greek customs and traditions have their roots in the Greek Christian Orthodox religion. The church plays an important role in the daily lives of the Greeks, and religion and tradition are intrinsically interwoven. Easter is the most important religious holiday in Greece, and is preceded by 40 days of fasting.

![[Demetrios and Rodopi Wedding]](../FamAngTakiWed.jpg) In 1937 at age 19 Rodopi Havas was married to Demetrios (Taki) Angelidis, the son of the local school teacher Eoulios Angelidis and his wife Marika.

Demetrios Angelidis, known as Taki, was the village's most handsome and most desirable bachelor.

In 1937 at age 19 Rodopi Havas was married to Demetrios (Taki) Angelidis, the son of the local school teacher Eoulios Angelidis and his wife Marika.

Demetrios Angelidis, known as Taki, was the village's most handsome and most desirable bachelor. ![[Marika and Ioulios]](../FamAngParents.jpg) According to mythology, Lemnos is the island of Hephaestus, the god of fire and volcanoes. A myth says that he landed on this island when Hera, his mother, threw him from Mount Olympus (where the Gods resided) because she found that he was an ugly baby. Hephaestus broke his leg when he landed on the island and stayed lame ever after. The people of the island took care of him and the god, in return, taught them his art of ironsmith. Archaeological excavations have brought to light early Bronze Age settlements at Poliochni.

According to mythology, Lemnos is the island of Hephaestus, the god of fire and volcanoes. A myth says that he landed on this island when Hera, his mother, threw him from Mount Olympus (where the Gods resided) because she found that he was an ugly baby. Hephaestus broke his leg when he landed on the island and stayed lame ever after. The people of the island took care of him and the god, in return, taught them his art of ironsmith. Archaeological excavations have brought to light early Bronze Age settlements at Poliochni.![[Taki hunting]](../FamAngTaki-2.jpg) World War II had isolated the island and its inhabitants. There was no incoming or outgoing mail. Rodopi remembered that the Germans required all citizens to surrender their guns. The penalty for concealing a weapon was execution on the spot. German soilders often killed villagers who were found not to be in compliance with German edicts. Gun shots were found often as were bodies of murdered victims. Demetrios had two guns which he used for hunting. He surrendered one but kept the other which he hid under the pavement at the entrance to the house. A rug made of dried sheep's skin covered the area. Demetrios's action upset Rodopi as it risked the lives of the entire household. One day two German officers approached the house. Rodopi was certain they had come to search for weapons. They stepped over the stone pavement which hid the gun and addressing her as "Fraulein" they announced they were taking an inventory of the house. They looked into each of the four rooms. They were actually doing a house to house search looking for rooms in which to board German soldiers. The Angelidis house had two bedrooms upstairs, one for the stepmother Koralia and the other by Demetrios, Rodopi and their son Xenophon. The downstairs rooms consisted of a living room and kitchen. The Germans departed the house without incident.

World War II had isolated the island and its inhabitants. There was no incoming or outgoing mail. Rodopi remembered that the Germans required all citizens to surrender their guns. The penalty for concealing a weapon was execution on the spot. German soilders often killed villagers who were found not to be in compliance with German edicts. Gun shots were found often as were bodies of murdered victims. Demetrios had two guns which he used for hunting. He surrendered one but kept the other which he hid under the pavement at the entrance to the house. A rug made of dried sheep's skin covered the area. Demetrios's action upset Rodopi as it risked the lives of the entire household. One day two German officers approached the house. Rodopi was certain they had come to search for weapons. They stepped over the stone pavement which hid the gun and addressing her as "Fraulein" they announced they were taking an inventory of the house. They looked into each of the four rooms. They were actually doing a house to house search looking for rooms in which to board German soldiers. The Angelidis house had two bedrooms upstairs, one for the stepmother Koralia and the other by Demetrios, Rodopi and their son Xenophon. The downstairs rooms consisted of a living room and kitchen. The Germans departed the house without incident.![[Demetrios, Rodopi, Xeny and Tom]](../FamAngBronx.jpg) Rodopi, with her 6 year old son Xenophon and stepmother Koralia moved into the apartment of Athanasios Havas, the brother of George Havas, at 1076 Simpson Street, in the Bronx where a large Greek community had settled. At the Greek Orthodox Church, Zoodochos-Peghe, located at 3573 Bruckner Blvd, she made friends with several Greek women who were employed as seamstresses in a Greek-owned shop named "Finishes" located at 46th Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City.

Rodopi, with her 6 year old son Xenophon and stepmother Koralia moved into the apartment of Athanasios Havas, the brother of George Havas, at 1076 Simpson Street, in the Bronx where a large Greek community had settled. At the Greek Orthodox Church, Zoodochos-Peghe, located at 3573 Bruckner Blvd, she made friends with several Greek women who were employed as seamstresses in a Greek-owned shop named "Finishes" located at 46th Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City. ![[Xeny and Tom - Birthday]](../FamAngTomXen.jpg)

![[Tom - Lemnos]](../FamAngTomLemnos.jpg)

![[Demitrios and Xenophone]](../FamAngTaki.jpg)

![[Viola and Xeny Wedding]](../FamAngXenWed.jpg)

![[George]](../FamAngGeo.jpg)

![[Mary Ellen and Bruce]](../FamAngMaryWed.jpg)

![[Tom and Angie]](../FamAngTomWed.jpg)

![[Tom Angelidis Family]](../FamAngTomFam.jpg)

![[Jimmy and Stacy]](../FamAngCollage.jpg)